Magnetic Impulses Help Create Muscle Activity Maps to Diagnose Motor Disorders

Using transcranial magnetic stimulation, Russians scientists were able to precisely track inter-muscle interactions between cortical representations of arm muscles. In the future, this method will help track brain changes in patients with motor disorders. The study was published in Human Brain Mapping. The project was supported by the Presidential Programme of the Russian Science Foundation (RSF).

Today, transcranial magnetic stimulation is actively used in psychiatry and neurology to treat depression, pain, and other conditions. But the method is still underused for the assessment of the motor cortex and musculoskeletal conditions in different disorders, exercise, or rehabilitation.

Russian researchers examined the reliability of motor mapping with the use of this method. The scholars managed to precisely track inter-muscle interactions between cortical representations of arm muscles. In the future, this will help track brain changes in patients with motor disorders.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) helps doctors and researchers activate the human cortex with short magnetic impulses. Today, this method is used in psychiatry and neurology to treat, for example, such conditions as depression, pain, Parkinson’s disease and many disorders. In addition, TMS looks quite promising in terms of brain research and its functional mapping — the creation of brain maps. Combining TMS with MRI navigation is particularly effective. This method is called navigated TMS or nTMS. For some tasks, it is more precise than other brain mapping methods, such as functional MRI. In nTMS, the motor cortex is stimulated. This leads to muscle contractions, which are assessed by researchers who register muscle electric activity. The spatial accuracy of nTMS mapping may be as small as two millimeters, and its results are called muscle cortical representation (MCR) or a TMS motor map. This approach may be used to assess motor cortex changes in different disorders, exercise, or rehabilitation.

Despite the advantages of nTMS mapping, in practice this method is rarely used. Further confirmation of data received with this method is needed. This issue was tackled by Russian researchers of the Centre for Cognition & Decision Making of HSE University’s Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience, the Research Centre of Neurology, and the Federal Centre of Brain Research and Neurotechnologies. They carried out a study of the absolute and comparative reliability of mapping data (muscle cortical representations) of arm muscles. For this purpose, they invited healthy male volunteers aged 19 to 33. None of them had any neurological or mental disorders; the scholars also excluded athletes, musicians, and surgeons, since they are likely to have highly precise motor function due to their work.

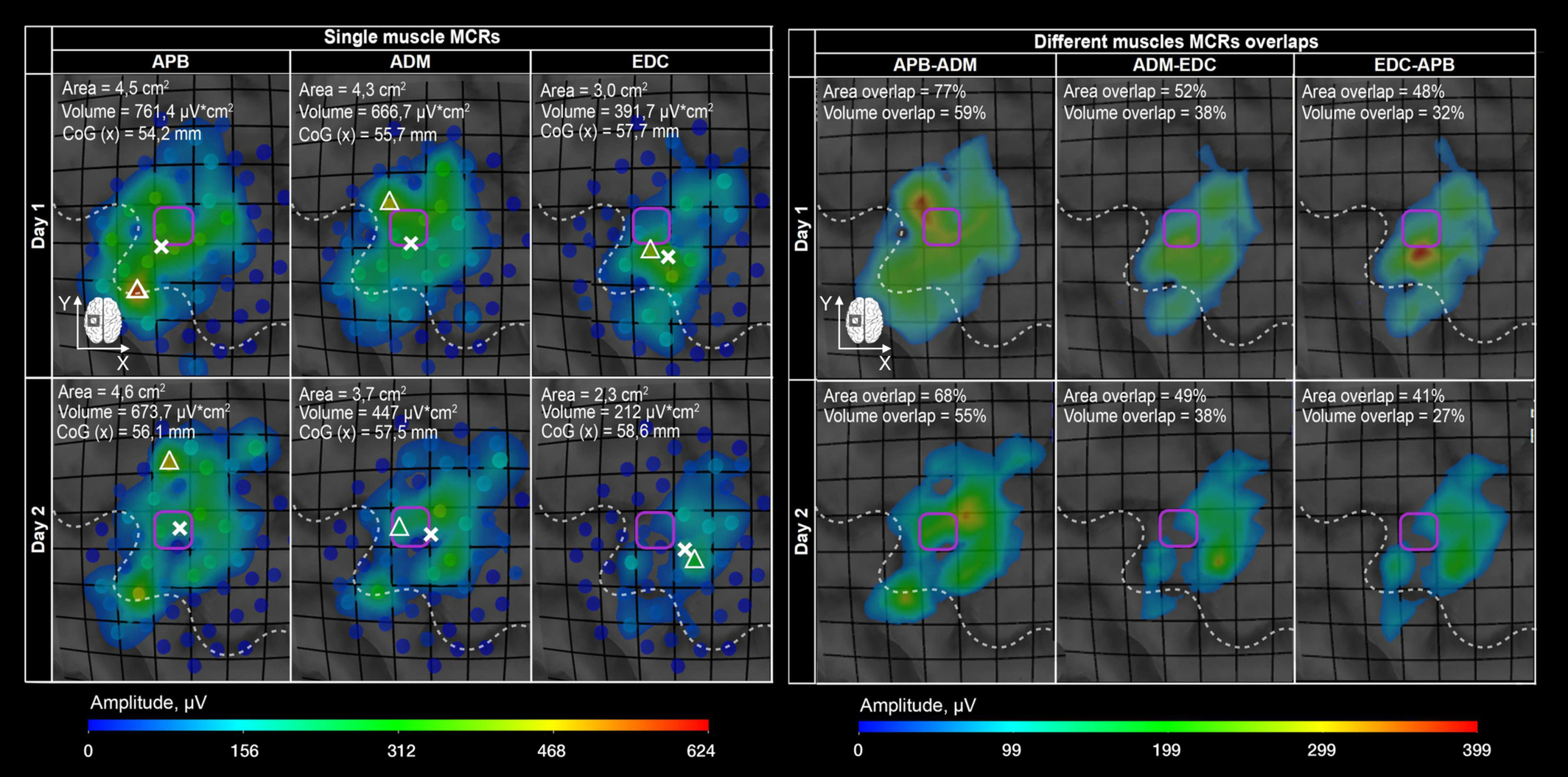

The volunteers participated in two nTMS mapping sessions separated by 5-10 days. The researchers registered contractions of three muscles that control the movement of hand and fingers. This way, they received TMS muscle cortical representations. Reliability analysis showed that the commonly used metrics, such as areas, volumes, and centres of gravity had a high relative and low absolute reliability for the muscles. The former assesses the results of repeated measurements, while the latter tracks the change of data in one participant. Overlaps between different muscle MCRs were highly reliable, which allowed the researchers to track the interactions between these maps.

Maria Nazarova

‘Our study is important not only for fundamental science. It also opens new opportunities for the use of nTMS motor mapping to evaluate cortical changes in healthy people and patients with neurological conditions, such as those who are undergoing rehabilitation after a stroke,’ said Maria Nazarova, head of the RSF grant project, Candidate of Science (Medicine), and researcher of the Centre for Cognition & Decision Making (Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience, HSE University) and the Federal Centre of Brain Research and Neurotechnologies.

Maria Nazarova

See also:

When Thoughts Become Movement: How Brain–Computer Interfaces Are Transforming Medicine and Daily Life

At the dawn of the 21st century, humans are increasingly becoming not just observers, but active participants in the technological revolution. Among the breakthroughs with the potential to change the lives of millions, brain–computer interfaces (BCIs)—systems that connect the brain to external devices—hold a special place. These technologies were the focal point of the spring International School ‘A New Generation of Neurointerfaces,’ which took place at HSE University.

How the Brain Responds to Prices: Scientists Discover Neural Marker for Price Perception

Russian scientists have discovered how the brain makes purchasing decisions. Using electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG), researchers found that the brain responds almost instantly when a product's price deviates from expectations. This response engages brain regions involved in evaluating rewards and learning from past decisions. Thus, perceiving a product's value is not merely a conscious choice but also a function of automatic cognitive mechanisms. The results have been published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Electrical Brain Stimulation Helps Memorise New Words

A team of researchers at HSE University, in collaboration with scientists from Russian and foreign universities, has investigated the impact of electrical brain stimulation on learning new words. The experiment shows that direct current stimulation of language centres—Broca's and Wernicke's areas—can improve and speed up the memorisation of new words. The findings have been published in Neurobiology of Learning and Memory.

HSE Researchers Discover Simple and Reliable Way to Understand How People Perceive Taste

A team of scientists from the HSE Centre for Cognition & Decision Making has studied how food flavours affect brain activity, facial muscles, and emotions. Using near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), they demonstrated that pleasant food activates brain areas associated with positive emotions, while neutral food stimulates regions linked to negative emotions and avoidance. This approach offers a simpler way to predict the market success of products and study eating disorders. The study was published in the journal Food Quality and Preference.

HSE Neurolinguists Create Russian Adaptation of Classic Verbal Memory Test

Researchers at the HSE Centre for Language and Brain and Psychiatric Hospital No. 1 Named after N.A. Alexeev have developed a Russian-language adaptation of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test. This classic neuropsychological test evaluates various aspects of auditory verbal memory in adults and is widely used in both clinical diagnostics and research. The study findings have been published in The Clinical Neuropsychologist.

Researchers at HSE Centre for Language and Brain Reveal Key Factors Determining Language Recovery in Patients After Brain Tumour Resection

Alina Minnigulova and Maria Khudyakova at the HSE Centre for Language and Brain have presented the latest research findings on the linguistic and neural mechanisms of language impairments and their progression in patients following neurosurgery. The scientists shared insights gained from over five years of research on the dynamics of language impairment and recovery.

Neuroscientists Reveal Anna Karenina Principle in Brain's Response to Persuasion

A team of researchers at HSE University investigated the neural mechanisms involved in how the brain processes persuasive messages. Using functional MRI, the researchers recorded how the participants' brains reacted to expert arguments about the harmful health effects of sugar consumption. The findings revealed that all unpersuaded individuals' brains responded to the messages in a similar manner, whereas each persuaded individual produced a unique neural response. This suggests that successful persuasive messages influence opinions in a highly individual manner, appearing to find a unique key to each person's brain. The study findings have been published in PNAS.

'We Are Creating the Medicine of the Future'

Dr Gerwin Schalk is a professor at Fudan University in Shanghai and a partner of the HSE Centre for Language and Brain within the framework of the strategic project 'Human Brain Resilience.' Dr Schalk is known as the creator of BCI2000, a non-commercial general-purpose brain-computer interface system. In this interview, he discusses modern neural interfaces, methods for post-stroke rehabilitation, a novel approach to neurosurgery, and shares his vision for the future of neurotechnology.

Smoking Habit Affects Response to False Feedback

A team of scientists at HSE University, in collaboration with the Institute of Higher Nervous Activity and Neurophysiology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, studied how people respond to deception when under stress and cognitive load. The study revealed that smoking habits interfere with performance on cognitive tasks involving memory and attention and impairs a person’s ability to detect deception. The study findings have been published in Frontiers in Neuroscience.

'Neurotechnologies Are Already Helping Individuals with Language Disorders'

On November 4-6, as part of Inventing the Future International Symposium hosted by the National Centre RUSSIA, the HSE Centre for Language and Brain facilitated a discussion titled 'Evolution of the Brain: How Does the World Change Us?' Researchers from the country's leading universities, along with health professionals and neuroscience popularisers, discussed specific aspects of human brain function.